Author: Adam Beaumont

While measures such as the WEF Index for gender equality are criticised, through that metric Iceland have been ranked as the most gender equal country in the world since 2009. For women’s football in UEFA they are regularly at the top end of pot 2 for qualification draws and have been to every European Championship from the same year. This is despite the fact that their population of ~370,000 is only above that of Andorra, Faroe Islands, Liechtenstein, San Marino and Gibraltar in the confederation! It would therefore be easy to assume that women’s football in the country followed a much easier development path to reach these heights. Unfortunately, such assumptions would be inaccurate, with Iceland’s women facing many familiar challenges.

The Beginning

While football came to the island in 1895, it took a while for organised football to start. The men’s league started in 1912, but was fragmented, with two seasons being won by default. The first evidence of women’s football appeared in 1914, when the team “Hvöt” (meaning motivation) formed in the town of Ísafjörður in the North-Western Vestfirðir peninsula, far away from the league in Reykjavík. Additionally, in the capital, Víkingur held training sessions for both genders despite not having appeared in the men’s league at the time. Neither situation would last long, with opinions of football being unhealthy or unsuitable for women starting to become prevalent. The women of the capital would only train for a few months and Hvöt disbanded after only a couple of years. The first ever match came on 12th July 1914, with two sets of the Hvöt girls playing each other. The oldest player was only 20, with the youngest being 11! Along with an unknown number of unofficial matches against local boys’ sides, their results were not recorded.

1940 saw a big change in women’s sport, but it was to football’s detriment. Handball leagues were started for both men and women, with the men’s league being larger but both playing on the same day. Therefore, despite some prejudice, handball rapidly became the team sport that women were “allowed” to play. Their access to facilities was limited, leading to them gaining the use of second/training football pitches in the summer, while the indoor handball pitches weren’t used. Interestingly, while the men played football, this led to a rise in popularity for field handball for women.

At some point, at the latest in the 1960’s, the fact that they were regularly allowed on football pitches (albeit typically poorer quality than the men) meant that several teams would warm up with some football. This was a humble restart to the game, but it would prove to be a more permanent beginning. By 1968, with UEFA’s and Europe’s attitudes warming to women’s football, the idea gained more traction on the island. The handball teams of Fram and KR (both Reykjavík clubs) played a friendly football match, with Fram predicting at their 60th football anniversary event that soon every club would have women’s teams at every level. The sports magazine Íþróttablaðið wrote a fairly positive piece in 1969, mentioning an Italy v Denmark international match, ending with the question: “Hvnær fáum við að sjá íslenzkt kvenfólk leika hér á Laugardalsvellinum?” (When will we see Icelandic women play at the Laugardalsvöllur?) Additionally, Valsblaðið published an interview with Sigrún Ingólfsdóttir, who was the first woman to referee a boy’s football match. She mentions that the players treated her normally, but others were definitely unhappy about a female referee.

Interestingly, 1970 saw fairly significant engagement by KSÍ (the Icelandic FA), with them starting to embrace the idea. Up until this point, the idea of women’s football hadn’t really been openly talked about, with merely an occasional newspaper mention of it being popular “elsewhere” and no real opinions expressed. However, with formal thought being applied by the federation, that led to more interaction on the topic. The newspaper Þjóðviljinn was fairly positive – albeit very sexist – stating that with most Icelandic football fans being of ‘the stronger gender,’ that watching ‘beautiful women’ play football should be popular. A 1972 opinion piece in Alþýðublaðið recognised women’s football as an area of strong interest, but was mainly focused on KSÍ’s governance.

As pressure rose, the football association made their first formal involvement, organising a friendly match of their own in the national stadium between a Reykjavík and a Keflavík XI. The Reykjavík XI won, though the actual scoreline does not appear to have been considered of note. This was on 20th July 1970, just before a men’s friendly match against Norway, allowing exposure to the audience of up to 5,822 for that match. While the match itself wasn’t treated fully seriously, with the referee wearing a detectives hat and it being used as a pre-match show, it did signify the changing attitudes. Alþýðublaðið mentioned in their article on it that “we mentioned the need to begin football for women and we encouraged leaders of clubs to give it due consideration” and “We hope to be able to report further on this in the near future.” However, the clubs themselves were still reluctant, as shown by their lukewarm response to the launch of the women’s football league in 1971. This was an indoor league, but only 10 sides signed up, with ÍR withdrawing before any matches were played.

Of the initial league sides (Ármann, FH, Fram, ÍA, Grindavík, Haukar, KR, Valur and Víkingur), only two were outside the capital region, with the girls of ÍA felling favourites Ármann, despite being the youngest team in the competition. Both Akranes (ÍA) and Grindavík are close to the capital and the geographical diversity couldn’t compete with the men’s league of the time, which had teams from around the island, but it was a promising start.

The League Truly Begins

By the next year, the league moved outside and this is viewed as the true start of the modern day Úrvalsdeild (or Premier Division). Ármann, FH, Fram, Grindavík and Haukar returned from the indoor league, with Breiðablik, Keflavík and Þróttur R being the new sides. Of these 8 initial participants, only Fram had ever won the men’s league before. In contrast Breiðablik, Grindavík and Keflavík were the only three sides to have not won a handball title (in either gender), showing some of its continued influence. Plenty of football players also continued to play other sports, such as current KSÍ chairwoman Vanda Sigurgeirsdóttir, who played both football and basketball.

From the first 5 seasons FH would win 4 titles, losing to Ármann in 1973, but then it was the turn of Breiðablik, who would take 6 of the next 7 titles. Breiðablik were relative unknowns, having never been successful in football, handball or basketball, but took advantage as the early title winners dropped off. FH would continue to play, but fell towards the bottom of the table, while Ármann would only play 3 seasons. This suggests that the clubs hadn’t greatly improved in attitude, with the league varying in size on an annual basis, clubs disappearing & reforming, and a relatively unknown team taking the glory.

The early star was Ásta Breiðfjörð Gunnlaugsdóttir, a terrifying striker for Breiðablik. She’d first appear at just 13 years old for the club, in 1974, and would go on to score 206 goals in just 181 appearances! The national side’s formation would add another 8 goals in 26 appearances, with her only missing 3 matches due to pregnancy. Her Úrvalsdeild scoring record would not be broken until 2001 and she would hold the national scoring record from partway into their debut match in 1981 until 1996. In 1981 itself, she would score 44 goals in just 17 league and cup matches, individually scoring more than half the teams in the league. The first woman to ever win Icelandic footballer of the year, beating out any of her male counterparts in 1994, Ásta B would be the only woman to ever do so, with the award splitting into male and female awards in 1997.

In an interview in 2006 (Morgunblaðið – 16.06.2006), she said she found it hard to quit football, even playing in a 2000 indoor tournament with Breiðablik. Proud of being one of the “pioneers” of the women’s game in Iceland, she also complimented how the FA had approached it, saying that they “got everything they needed” before the debut national match. However, white shirts in rainy weather were less fondly remembered!

Regardless, in 1978, the capital powerhouse Valur became the first team to have won a men’s and women’s title, though they failed to add to that on the women’s side until 1986. The second team to ever do so would be ÍA from Akranes in 1984 (the first club outside the capital to do so) and then the third, KR in 1993, with title winners becoming a bit more variable from 2000 onwards. The women’s cup was created in 1981 and the following year saw the expansion of the women’s league into 2 tiers, with the second tier having as many as 12 teams as early as 1986! Clubs remained inconsistent though, with the 1989 edition of the second tier having only 2 clubs, though numbers rapidly picked back up.

In the modern era, with the 2016 second tier having 22 clubs, the league expanded out into the 3 tiers that we see today, with a record 33 clubs in 2021 and 2022. The dream of every club having women’s teams is still far from realised though. For example, traditional heavyweights like Vikingur and Fram still don’t have a consistent team (both reformed in 2020), with Fram having folded several times in their history. In 1990 there were 70 men’s clubs to only 20 women’s clubs and in 2021 the 5 tiers of men’s football had 81 clubs, over twice that of the women’s leagues.

Some of the growth in the 1990’s can be attributed to the corresponding growth of the sport in the United States. With many US universities offering large numbers of football scholarships to women, this applied to foreign students as well. Therefore it became a viable route for Icelandic women footballers, who could receive a guaranteed, high standard education, while also continuing with the sport. This helped open up football to those whose parents were reluctant and several such footballers, upon returning home, would then go onto successful, high profile jobs, irrespective of their footballing success.

Even in the 1990’s though, it wasn’t plain sailing. In an interview with Íþróttablaðið on 01.06.1992, Vanda Sigurgeirsdóttir stated that there were still men who hated women’s football. She also criticised the lack of an U20 national side, leaving a large gap between the U16s and the senior squad. However, there were positives to take from the situation. The fact that she would go on to quit basketball, seeing more potential in football, shows that the sport was truly establishing itself. This was further proved by the leagues consistently having over 20 teams in total across the whole decade, only dropping to 19 in 2000 and 17 in 2001 before recovering once more.

Unlike the men’s league, the women’s league was able to start with a bit of geographical variety in teams. Sadly this was still a slow process with the initial league only having teams from Reykjavík (and the rest of the capital region), Keflavík and Grindavík. The second season brought in ÍA from Akranes, but it took until the 1982 expansion to see true variety. 1982 saw the two Akureyri clubs (Þór and KA) joining, along with BÍ Ísafjörður from possibly the spiritual home of Icelandic women’s football. Súlan Stöðvarfjörður would add the first truly Eastern club in 1983 and from then on the map has gradually filled in. The other major footballing landmark, Vestmannaeyjar, the island home of ÍBV from the inaugural men’s season, remained outside of the women’s football map until 1987. Even then they only played the one season, with more consistent appearances from 1994 onwards. In the modern day, Vestfirðir itself no longer has a women’s team representing it, after the collapse of even the merged team BÍ/Bolungarvík in 2015/16, but otherwise the leagues cover the island.

Analysing performances over the years, Breiðablik are the only club to have played every season. They were relegated once, in 1987, but bounced back instantly, scoring 53 goals and conceding only 3 in 8 matches! This means that no current club has always been in the top division. FH only missed the seasons from 1990-92, but have not been successful since those first few years; Valur and KR have not missed a season since they joined, in 1977 and 1981 respectively; with Stjarnan being the final club with at least 40 seasons under their belts. Other big names have either appeared too inconsistently, have never had a significant women’s side or have been victims of the many mergers in the Icelandic women’s game. An example of mergers are Þór/KA, the combined Akureyri club, who are the only club not from the South-West to win a title.

The Women’s Champions’ League

Valur Reykjavík became the first Icelandic side to reach the knockout stages of the Women’s Champions League, in 2005-06 after making their way through both qualifying rounds, but subsequently were annihilated 19-2 by Turbine Potsdam. Margrét Lára Viðarsdóttir led the line for Valur, becoming the competition’s top scorer that year, a feat she would replicate for both seasons of her return to the team across 2007-08. However, they’d fail to replicate their earlier success in both years, falling just short of the group stages. She’d go on to become a sensation in Icelandic football, retiring in 2019 with 79 goals from 124 national appearances. She also became the third woman to beat Ásta B’s scoring record in the Úrvalsdeild, doing so in 2008, and having the highest goals per game average of anyone in the top 20.

From 2009-10 to 2019-20, an Icelandic side reached the Round of 32 every year for the Women’s Champions’ League, with 2010-11 and 2011-12 seeing them briefly feature in UEFA’s top 8 country rankings and getting two clubs participating. Valur, Breiðablik, Þór/KA and Stjarnan all took part at least once, with 2017-18 and 2019-20 seeing further progression to the Round of 16! The latest format changes have seen Iceland return to 2 sides, though Valur fell in the qualifying stages and Breiðablik scored only a solitary point in the groups.

The National Side

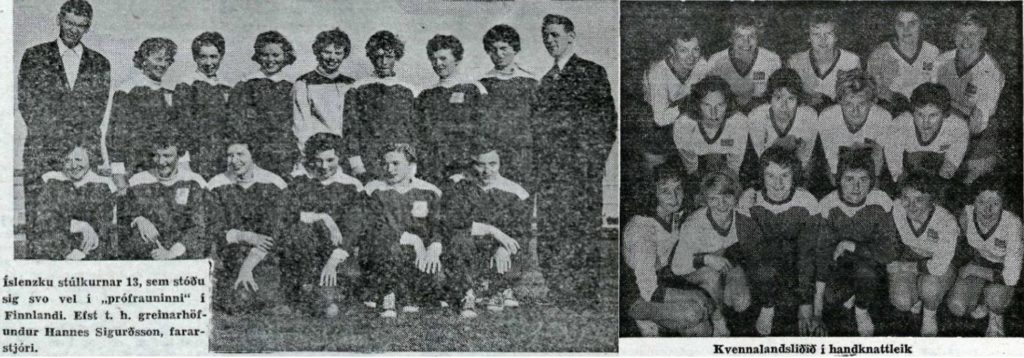

Top row, left to right: Guðmundur Þórðarson (coach), Kristín Reynisdóttir, Kristín Aðalsteinsdóttir, Sigrún Blómsturberg, Hildur Harðardóttir, Svava Tryggvadóttir, Jónína Kristjánsdóttir, Bryndís Valsdóttir, Sigrún Cora Barker, Ásta B. Gunnlaugsdóttir, Svanfríður Guðjónsdóttir (KSÍ), Sigurður Hannesson (coach), Gunnar Sigurðsson (KSÍ)

Bottom row, left to right: Unknown, Brynja Guðjónsdóttir, Magnea H. Magnúsdóttir, Ragnheiður Jónasdóttir, Guðríður Guðjónsdóttir, Ásta M. Reynisdóttir, Bryndís Einarsdóttir, Ragnheiður Víkingsdóttir, Rósa Á. Valdimarsdóttir

The introduction of the cup competition and the upcoming expansion of the league into 2 divisions saw KSÍ form the first national side in 1981, playing a single friendly against Scotland before attempting to qualify for the inaugural women’s Euros in 1984. The 1981 friendly was close, with only two late goals undoing the side, a lack of stamina towards the end of the match forcing Iceland to pay the price. In the qualifiers, in contrast, they sadly failed to score a single point and turned to friendlies for further development. September 1987 saw the start of a gap in women’s national football, with the under 16s playing in 1990 and 1991, but the senior side not returning until May 1992! KSÍ records state that it was due to a lack of funding, though the matches played by the men’s youth teams, particularly those overseas, would seem to suggest a different story…

Nonetheless, they returned for the 1993 Euros qualifiers, coming a distant second from England, but ahead of Scotland in a 3 team group. Since then, they’ve entered every major tournament qualification. 1995 saw them comfortably win their group, with narrow victories over the Netherlands and heavy ones over Greece. However, they fell in play-offs for the 1995 Euros (which would’ve also meant a World Cup spot), by losing 2-1 in both legs to England. There was a similar story in the Euro 1997 qualifiers, with Iceland being drawn as a “Class A” team, with the group winners qualifying directly and play-offs between 2nd and 3rd places. Familiar home and away wins over the Netherlands all but guaranteed them 3rd, though against France and Russia they only managed a home draw against the French. This nonetheless put them into a play-off against Germany, who’d finished just behind world champions Norway, and they lost 3-0 and 4-0 in a heavy aggregate defeat.

Between their group and play-off matches for 1997 qualifiers they made their Algarve Cup debut in 1996. A victory over Finland in an all-Nordic group was followed up by a penalty shoot-out loss to Russia to finish 6th. They returned in the next year, but in the same group they failed to get a point and had to beat Portugal on penalties to avoid last place. This signalled the beginning of a slight downturn in their fortunes, with lacklustre results across the 1999 and 2001 qualifiers, leading to them finishing outside of the play-offs in 1999 and in the relegation play-offs in 2001. After a 2-2 draw in Romania, they managed 6 goals in the second half of their home leg to thrash them 8-0 and stay in the top UEFA classification.

As the sport continued to grow, both at home and across Europe, Iceland started to see more interest in the team. 2003 qualifiers saw them disappointingly draw at home to Russia, but then over 1,000 spectators saw them beat Italy and over 2,000 saw them beat Spain! Away draws to Russia and Spain cemented them a play-off spot against old enemies England. A late English goal led to a 2-2 draw in Iceland, with a similarly late goal sealing a 1-0 loss in England to send them narrowly out.

The team also managed to secure a play-off spot in the 2005 qualifiers, with the reintroduction of 3rd place ensuring one. They again managed only a singular point against France and Russia (once again), but were comfortable facing Poland and Hungary, setting a new personal record with their 10-0 home win against the former. However, in the play-off, Norway would go on to annihilate them 7-2 in Reykjavík, with the 2-1 loss in Oslo merely a formality after that point. With only group winners qualifying in 2007 qualifiers, Iceland’s 3rd place finish wasn’t enough, with comfortable performances over the lower ranked sides but falling short of the top seeds once more.

2006 also saw the team’s return to the Algarve Cup, though they would stop again after the 2019 edition. While they would be in the penultimate positional play-off 7 times from those 13 appearances, they were never in the bottom two places. A 2nd place finish in 2011 followed by two 3rd place finishes in 2014 and 2016 show their competitiveness, particularly considering they were never ranked in the top half of the tournament by the FIFA rankings.

Top row, left to right: Katrín Jónsdóttir, Edda Garðarsdóttir, Katrín Ómarsdóttir, Þórunn Helga Jónsdóttir, Sara Björk Gunnarsdóttir, Dóra María Lárusdóttir

Bottom row, left to right: Ólína Guðbjörg Viðarsdóttir, Hallbera Guðný Gísladóttir, Guðbjörg Gunnarsdóttir, Sif Atladóttir, Margrét Lára Viðarsdóttir

The national side caught the imagination of the nation with their successful qualification for the 2009 Euros. Þóra Tómasdóttir, confident in their qualification hopes, followed and filmed the team throughout, leading to the creation of the film Stelpurnar Okkar or “Our Girls” to immortalise their journey. 2017 would see the book of the same name published, as a full history, going back all the way to 1914. In qualification, 6 wins and 2 losses (both away, to France and Slovenia) left them comfortably in 2nd place and well within the play-off spots. A 4-1 aggregate victory over the Republic of Ireland sent them to a first major tournament for an Icelandic national side. It would take a further 7 years for the men to follow in their footsteps.

Similarly, a play-off victory sent the team to the 2013 Euros, with consecutive 3-2 victories over Ukraine. They managed to beat out Scotland on goal difference in their 2017 Euros qualifiers to win a qualification group for the first time, though the expansion of the Euros to 16 teams meant that second place would’ve been sufficient. This proved to be the case in 2022 (2021 Euros) too, meaning that they’ve qualified for every Euros since 2009, though a World Cup spot remains elusive.

Other National Football

National youth football started off more slowly, though that was the case for tournaments too, so this can’t necessarily be attributed to KSÍ. They are regulars in the annual U16/U17 Nordic Cup, joining from the 3rd tournament in 1990, and played in every of the U20/U21 Nordic Cups from the 4th edition in 1993 until it became an U23 tournament in 2007. While they tend to finish towards the bottom of both tournaments, it should be noted that the invited sides were often very highly ranked so this is not necessarily a bad thing. They have attempted to qualify for every UEFA women’s youth championship at both age levels since their beginnings in 2008 (U17) and 1998 (U19).

As the senior side started to peak, their youth teams met with some success too. The U17s qualified for the 2011 UEFA Championship, finishing in 4th place, and hosted the 2015 edition, but fell in the group stages. The U19s hosted the 2007 Euros and qualified for the 2009 edition, but fell in the group stages both times. Both teams are consistently competitive in qualifiers, but, as with the senior team in World Cup qualifiers, tend to fall short of the tournaments as the small number of teams makes them tricky to qualify for.

As the profile of the women’s game has risen, youth team friendlies have become a little more common too. Icelandic sides have played at every level, from the U15s winning a 2019 mini-tournament in Vietnam, to a handful of U23 friendlies. The U15s, U18s and U23s have not played much, though the lack of competition for women’s U23 sides and for U15 and U18 sides in general are significant factors here. The only significant oddity is a recorded U17 friendly in 1993, 10 years prior to their next matches in the 2003 European Youth Olympics and 4 further years prior to consistent match time! However, the U16 side were consistently active across the intervening years so this should not have had any negative impact.

Even with the expansion of UEFA into women’s futsal in 2019, Iceland are not expected to participate in the near future, if ever. The prevalence of full-size indoor pitches largely eliminated the sport in the country, with even the men’s national futsal side only ever playing 3 recorded international matches to date – in Euro 2012 qualifiers.

Further Notable Players

Despite starting 35 years after their male counterparts and playing under 300 total matches, the women’s senior national side has 12 centurions, compared to the men’s 3 (2 within 2021). All have played multiple seasons outside of Iceland, mainly in Scandanavian leagues but also with teams in Germany (Wolfsburg, Duisburg, Potsdam, Bayern), France (Lyon, Marseille), England (Chelsea, Reading, West Ham) and the USA (Philadelphia Independence, Portland Thorns).

4 players have won multiple women’s footballer of the year awards as of the end of 2021. They have been:

Ásthildur Helgadóttir

The majority of her playing career was spent alternating between Breiðablik and KR, often competing for the golden boot and twice winning it. As of the end of 2021 she stands in 9th place in the overall goalscorer table, with 133 goals in 153 appearances. Outside of Iceland she spent part of the 2001 season in the USA and finished her career with 46 goals in 58 appearances for Swedish side Malmö. On the international level she’d be the first person to ever score for the U21 side in 1993 and would fully secure the scoring record at that level in 1996. For the senior side, she’d break Ásta B’s scoring record in 1996, amassing 69 caps and scoring 23 times. While both of these records would fall, it would take another decade, showcasing her clear dominance on the frontlines for Iceland across her career.

Margrét Lára Viðarsdóttir

A lethal striker, Margrét Lára would win 5 footballer of the year awards, become the first female footballer to win the Icelandic Sportsperson of the Year Award, and shatter records. Mainly playing at Valur and Kristianstads DFF, she would be: the top scorer in the Champions League 3 times and the Icelandic league 5 times; would become the second highest ever scorer in said division; and hit scoring records for the national side at U17 (for 4 years), U19 (for 3.5 years), U21 (held since 2006) and senior level (held since 2007, over double her closest competitor); as well as be the youngest Icelander of either gender to ever score a senior international goal. Instrumental in Valur becoming the first Icelandic side to reach a European knockout round and peerless for the national side in terms of goalscoring ability, it is hard to see some of her records ever toppling.

Þóra Björg Helgadóttir

Some things run in the family – Þóra Björg is Ásthildur Helgadóttir’s sister! Debuting in the Icelandic league at the age of 14 with Breiðablik, she’s won 8 league titles with them and KR. Further afield she’s been the Player of the Year in the Norwegian league with Koboltn, twice goalkeeper of the year in the Swedish league and won 3 titles with Malmö, even playing as far afield as Australia! Iceland’s only centurion goalkeeper, she’s managed 108 caps and even a penalty goal against Serbia. Iceland have had several very safe pairs of hands between the sticks for them, but there have been none safer than Þóra Björg.

Sara Björk Gunnarsdóttir

Iceland’s record cap holder, winner of a record 7 Icelandic women’s footballer of the year awards, twice a Champions League finalist, winning one – is there anything Sara Björk cannot do? She’d debut for Haukar’s senior team at the age of just 14, move to Breiðablik at 18 and move to Sweden’s Rosengård just three years later. After winning 4 titles she’d earned a move to Wolfsburg, in Germany, which would bring her 4 more titles, 4 cup victories and deep progression in the Champions League. Today she plays for Lyon, in France, adding a Champions League title and a French title to her name. Only the second female footballer to win the Icelandic Sportsperson of the Year Award, she’s even done so twice, which no Icelandic footballer can beat.

One thing is for sure though. No matter how great several of these players have been, Iceland succeed as a team. There are countless names that could be added to any similar list and with several such names moving into coaching positions in Iceland or, in the case of Vanda Sigurgeirsdóttir, the chairmanship of KSÍ itself, we can expect many more names to join as the years go by.

Conclusion

Overall, for all that there was initial reluctance towards women’s football, and that it only really started when the authorities in UEFA and KSÍ were looking upon the idea more positively, women’s football is thriving in Iceland. They are consistently competitive at a national and a club level, but have a much smaller population and so tend to struggle with the most established teams. The new generation includes young stars like Karólína Lea Vilhjálmsdóttir at Bayern Munich, Amanda Andradóttir, who was chased by the Norwegian FA for their national side and Sveindís Jane Jónsdóttir, the latest Icelandic women’s footballer of the year, at Wolfsburg. The future looks bright. As women’s football continues to expand, don’t be surprised to see them at more tournaments, with perhaps that World Cup debut being on the horizon soon.

With thanks to Stefán Pálsson, Orri Rafn Sigurdarson, Ómar Smárason (KSÍ), the staff at Þróttur R and others. Speakers of Icelandic are recommended to read the fantastic Stelpurnar Okkar by Sigmundur Ó. Steinarsson, which will cover this topic in vastly more detail.

Top row, left to right: Sveindís Jane Jónsdóttir, Karólína Lea Vilhjálmsdóttir, Alexandra Jóhannsdóttir, Glódís Perla Viggósdóttir, Ingibjörg Sigurðardóttir, Gunnhildur Yrsa Jónsdóttir

Bottom row, left to right: Elísa Viðarsdóttir, Sif Atladóttir, Cecilía Rán Rúnarsdóttir, Svava Rós Guðmundsdóttir, Agla María Albertsdóttir

[…] Die Geschichte des isländischen Fußballs der Frauen (Adam Beaumont, Forgotten Heroines) [Longread, Englisch] […]